C64 invitation cracked!

On request, this is a brief writeup of my adventures cracking the hidden part

of the Datastorm 2017 Summer invitro by Fairlight. Spoilers ahead!

Having discovered the password entry screen that appears when you press space

during the end scroller, I quickly dived into the monitor and began to explore

the code. It became apparent that the password was used as the key for a very

professional-looking encryption algorithm (I later learned that it’s known as

RC4).

I spent a lot of time trying to reverse the cipher, but couldn’t find any

obvious weaknesses. And you simply can’t brute-force a 16-character password:

There are about 2^80 possibilities, and merely counting to that number on a

1 GHz processor would take 40 million years. And I only had two weeks.

But I noticed something interesting: The drive LED was making irregular

patterns of short and long flashes. Hmmm! I’m not skilled at reading Morse code

quickly, but it was easy enough to patch Vice to create a log file of all the

LED transitions with timestamps. Then I used “R”, the statistics program, to

visualise the data as a signal trace. Using Wikipedia’s Morse chart as a

reference I managed to decode something like:

LEGENDS NEVER DIE / FILTER / LIGHTHOUSE / TORUS / DISCO / STRING / SEVENTEEN /

FAIRLIGHT / NU

I jumped to the conclusion that “FAIRLIGHT NU” was just an advert for the

group’s regular site, and that the rest of the message was directly related to

the password. But when that didn’t yield any results, I briefly compared notes

with soci (hi!), who supplied the vital piece of information that the Morse

code message was pointing to a website with numbers on it. Knowing that, it was

straightforward to figure out that some of the spacing characters were dashes

and periods, and hence what the full domain name was supposed to be.

And sure enough, the site contained 19 large hexadecimal numbers of varying

lengths. What could they mean? Two of them began with “ea”, the opcode for the

NOP instruction, but overall they didn’t appear to be 6502 code. On a whim, I

googled the first number, and found a page that listed a lot of dictionary

words along with their MD5 and SHA-1 hashes. It turned out that the first two

numbers were the SHA-1 hashes of “alfa” and “bravo”. The remaining numbers

didn’t appear in Google’s index, except one which returned a small, unrelated

image. I later found out that this was the SHA-256 hash of the word “six”, so

presumably somebody was generating thumbnails with hash-based filenames, or

something along those lines.

But by now, all the evidence was pointing in one direction, so I wrote a bash

script that used the unix tool “shasum” to compute a variety of SHA-hashes for

the complete NATO phonetic alphabet, and check them against the list of

numbers. Sure enough, all nineteen numbers turned out to be hashes of code

words from that very alphabet. The first three (alfa, bravo, charlie) seemed to

serve as a hint to get people started, and the remaining sixteen, although they

didn’t spell out a regular word, were indeed the secret password that decrypted

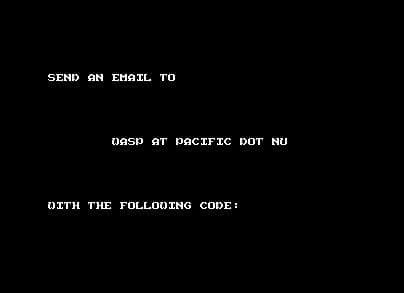

the hidden part, in which a scroller told me to mail a secret code to wasp in

order to claim the golden ticket.

By now I had been staying up way too far into the early hours of the night, so

I sent the mail and promptly fell asleep. The next day it struck me that the

Commando music had been hinting at a military theme all along, perhaps

subconsciously priming my mind for Morse code and phonetic spelling alphabets.

All in all, this was an enjoyable and, yes, t-t-t-tricky challenge. Thank you

very much, moh and company!

LFT